The 24-Cell

The 24-cell is a regular 4D polytope bounded by 24 octahedra, 96 triangles, 96 edges, and 24 vertices. It is a unique object with interesting properties that set it apart from other polytopes.

The regular polygons in 2D exhibit a property known as self-duality: exchanging their facets and vertices result in the same polygon. In all other dimensions above 2D, the only regular self-dual polytopes in all dimensions are the simplexes (tetrahedron, 5-cell, ... etc.), with one exception: the 24-cell.

In 2D, the regular polygons that can tile 2D space are the triangle, square, and the hexagon. In 3D and beyond, the only regular space-tiling polytopes are the hypercubes, but in 4D, there are two special tilings: the 24-cell tiling and its dual 16-cell tiling.

The closest 3D equivalent of the 24-cell is the rhombic dodecahedron. Both can tile their respective spaces, but the rhombic dodecahedron is neither regular nor self-dual. The 24-cell is both.

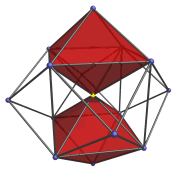

Vertex-first projections

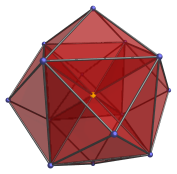

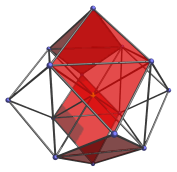

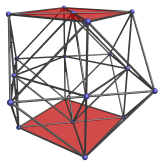

The vertex-first orthographic projection of the 24-cell has a rhombic dodecahedral envelope. The following image shows this projection, with hidden cells omitted.

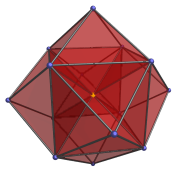

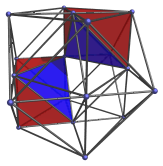

The nearest vertex is at the center of the envelope where the 8 internal edges meet, shown here in yellow. It may be thought of as the ‘north pole’ of the 24-cell. There are 6 octahedra (slightly flattened by the projection) packed around it in a cubic symmetry, as shown in the images below.

These are the ‘northern cells’.

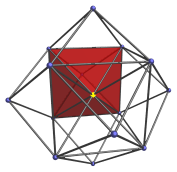

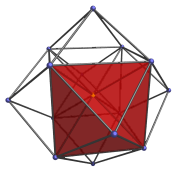

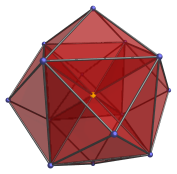

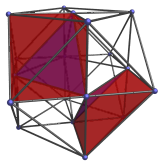

Each of the 12 faces of the rhombic dodecahedron in the orthographic projection corresponds with an octahedral cell lying at the “equator” of the 24-cell. They are shown in the following images:

They appear flat because they lie at a 90° angle to the 4D viewpoint. On the other side of 24-cell, there another 6 cells arranged in cubic symmetry around the “south pole” vertex, mirroring the 6 northern. This makes a total of 24 cells.

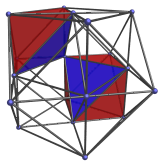

The vertex-first perspective projection of the 24-cell has a similar structure, except that the 12 equatorial cells are hidden from view, and the faces of the rhombic dodecahedron aren't quite flat, making the shape of the projection envelope a tetrakis hexahedron. The following image shows this projection:

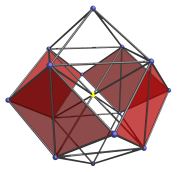

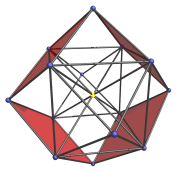

Cell-first projections

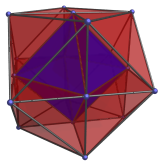

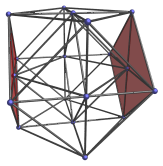

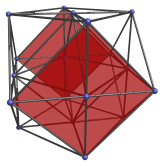

The cell-first parallel projection of the 24-cell has a cuboctahedral envelope, as shown in the following image:

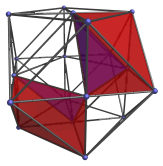

The closest cell to the viewer lies in the center of the image, shown here in blue. Surrounding it are eight octahedra, shown in the following images:

These octahedra appear to be irregular, but this is just an artifact of the perspective projection. They are perfectly regular octahedra in 4D space.

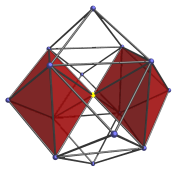

At the vertices touching the central blue octahedron are another six octahedra, shown in the following images:

These cells lie on the limb of the 24-cell. They appear flattened into squares because they are seen from a 90° angle.

Past these cells, on the far side of the 24-cell, lies another 9 cells mirroring the layout of the previous 9 cells. This makes a total of 24 octahedral cells.

The cell-first perspective projection of the 24-cell has a similar layout of cells, except that the 6 equatorial cells are out of view, and the faces of the cuboctahedral envelope are slightly curved into pyramids, making the shape of the envelope a tetrakis cuboctahedron. The following image shows this projection:

Construction

One possible way to construct the 24-cell is by a process analogous to the construction of the rhombic dodecahedron in 3D. That is, by cutting the 4D hypercube into 8 cubical pyramids and attaching them to the faces of a second 4D hypercube. This construction is easiest to understand if one compares the cell-first projection of the hypercube and the vertex-first projections of the 24-cell. It gives the coordinates of the 24-cell as all permutations of coordinates and changes of sign of:

- (1,1,1,1)

- (2,0,0,0)

These coordinates give an origin-centered 24-cell of edge length 2.

Another construction is via the rectification of the 16-cell. Rectification is to cut off the vertices of a polytope such that the cutting hyperplane lies on the midpoints of the edges meeting at the vertex. This construction is easiest to understand if one compares the vertex-first projection of the 16-cell and the cell-first projection of the 24-cell. Starting from a 16-cell with radius 2 (which has coordinates (2,0,0,0) with its permutations and changes of sign thereof), the coordinates of the 24-cell thus derived are all permutations and changes of sign of:

- (1,1,0,0)

These coordinates describe a 24-cell that is dual to the one described by the first set of coordinates. Its edge length is √2.

Geometric Properties

Decomposition into 16-cells

The first set of coordinates given in the previous section give us an interesting insight into the 24-cell: the permutations of (2,0,0,0) is a 16-cell of radius 2, and the changes of sign of (1,1,1,1) is a tesseract. A tesseract can be decomposed into two 16-cells by alternation: the changes of sign of (1,1,1,1) with an even number of negative signs describe a 16-cell of radius 2, and the changes of sign of (1,1,1,1) with an odd number of negative signs describe another 16-cell of radius 2. So we see that the 24-cell can be decomposed into three 16-cells.

An equivalent decomposition of the dual 24-cell into three 16-cells can be derived as follows: the dual 24-cell has the coordinates (1,1,0,0) with all permutations of coordinates and all changes of sign thereof. We may, for example, pick (1,1,0,0) itself as a point in the first 16-cell in the decomposition. Its antipodal point, (−1,−1,0,0), obviously also belongs to the same 16-cell. The remaining 6 points must lie on the hyperplane orthogonal to these two antipodal points, so they must be precisely those points whose dot products with these two points are 0, namely, (−1,1,0,0), (1,−1,0,0), and (0,0,±1,±1). Collecting all of them, we see that the first 16-cell's coordinates must be:

- (±1, ±1, 0, 0)

- (0, 0, ±1, ±1)

This implies that the second 16-cell's points must come from a different permutation of coordinates of (1,1,0,0), such as (1,0,1,0). A parallel argument then leads us to conclude that its coordinates must be:

- (±1, 0, ±1, 0)

- (0, ±1, 0, ±1)

The last possible set of permutations of (1,1,0,0) that do not belong to these first two sets are therefore:

- (±1, 0, 0, ±1)

- (0, ±1, ±1, 0)

It can be easily verified that these are the coordinates of a third 16-cell.

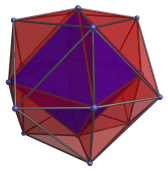

Coherent Indexing

Given a 24-cell, we can decompose it into three 16-cells and color its vertices based on which of the three 16-cells it belongs to, say red for the vertices of the first 16-cell, green for the vertices of the second, and blue for the third. Then every triangular face of the 24-cell will have vertices of 3 different colors, and we can assign a cyclic order to each triangle, say red-green-blue, and based on this order assign a direction to each edge. This is called a coherent indexing of the 24-cell's edges.

If we divide the edges in the Golden Ratio according to the direction assigned by this indexing and truncate the 24-cell at the points of division, then each of its 24 octahedral cells become 24 regular icosahedra, and in the place of the 24 vertices there will be 24 tetrahedra. The remaining gaps can then be filled up by 96 more tetrahedra, resulting in a semi-regular polychoron known as the snub 24-cell. If we now add to the snub 24-cell the vertices of the dual 24-cell, that effectively adds 24 icosahedral pyramids to it, turning it into a 600-cell.