4D Visualization

Interpreting 4D Projections (1)

Thus far, we have seen a few examples of 4D objects projected into 3D, as well as various methods of enhancing the images so that they are easier to understand. But how exactly does one interpret these images? What do the various features we find in these images really mean? We shall discuss this now.

Thinking in Terms of Volumes

When we first introduced dimensional analogy, we discussed the boundaries of objects in different dimensions. In 1D, objects are bounded by points, which are 0D constructs. In 2D, objects are bounded by lines and curves, which are 1D constructs. Similarly, in 3D, objects are bounded by surfaces, which are 2D constructs. This pattern led us to conclude, via dimensional analogy, that 4D objects must be bounded by volumes. Let's see how this helps us interpret a 4D projection.

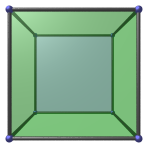

We'll begin by looking at the following perspective projection of the 3D cube:

This image consists of a number of parts: the outer boundary, which is a large square; a smaller blue square in the center; and four green trapezoid pieces connecting the outer square to the inner square.

Now, we know from our experience with 3D that the outer square corresponds with the near face of the cube, and the inner square corresponds with the far face of the cube. Although the outer square is larger than the inner square, in actuality the near and far faces of the cube are the same size. The far face only appears to be smaller because it is farther away in the 3rd direction.

Similarly, we know from our experience that the four trapezoid pieces between the inner and outer squares are really square faces of the cube. They only appear as trapezoids because they are being seen from an angle.

We also know that all these 6 faces of the cube are only on its outside. This is obvious to us, but it is very hard for a 2D being to understand. Upon examining the image, the 2D being will find that the inner square is completely inside the outer square. So how can it be only on the boundary of the cube? Keep this in mind as we now turn to examine the analogous situation in 4D.

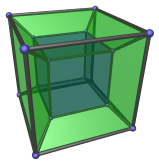

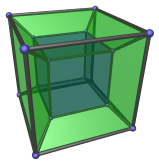

The following image shows a cell-first perspective projection of the 4D hypercube.

Let's compare this image bit by bit with the previous one, using dimensional analogy.

Firstly, we see that it contains two cubes: an outer cube, and a blue inner cube. The inner cube is the analogue of the inner square in the previous image. It is the far cell of the hypercube, just as the inner square is the far face of the cube. Similarly, the outer cube is the analogue of the outer square in the previous image. It is the near cell of the hypercube. These two cubes are in fact the same size; the blue cube only appears to be smaller because it is farther away in the 4th direction.

Secondly, there are 6 green frustum-shaped volumes that connect the outer cube to the inner cube: one on top of the inner cube, one underneath, and four around the sides. These frustums are the analogues of the trapezoids in the previous image. By dimensional analogy, we realize that they are actually not frustums; they are also perfect cubes identical to the inner and outer cubes. They only appear as frustums because they are being seen from an angle.

Finally, all 8 cubes, inner, outer, top, bottom, left, right, front, and back, are only on the outside of the hypercube. They are the equivalents of the faces of the cube. This is not easy to comprehend at first. From our perspective as 3D beings, these cubes have already completely filled up the cubical space occupied by the image; how can they only be on the outside of the hypercube?

To gain more insight into this perplexing question, let's take a deeper look at another feature of these images.

Where is the Inside?

Look again at the projection of the 3D cube. As 3D beings, we know that the inside of the cube lies in the volume between the 6 faces of the cube. But if a 2D being were to examine this projection of the cube, this “inside” would be rather elusive. Since the entire image is contained inside the outer square, it might think that the “inside” is simply the four trapezoids and the inner square. Upon being told that the inside of the cube lies between the inner and outer squares, it might incorrectly think that you are referring to the area covered by the 4 trapezoids. However, as we know, this is not the case; the 4 trapezoids are also only the boundary of the volume inside the cube. This is hard for the 2D being to understand. The 6 faces already fill up the entire square area of the image; where else is there space for the inside of the cube?

The answer, of course, lies in the fact that there is 3D depth involved here. The inner square is deeper in the 3rd direction than the outer square; so there is lots of room between them for the inside of the cube. In fact, the amount of room available is the sum total of all possible squares that lie between two opposite faces, as shown by the following animation:

The magenta square is moving back and forth between the left and right faces of the cube. Can you see how it sweeps out the volume enclosed inside the cube?

Now look at the 4D case.

Where is the inside of the hypercube? Dimensional analogy tells us that it must lie “between” all 8 cubes that form the boundary of the hypercube. However, when we look at the image above from our 3D perspective, we can see nowhere for this “inside” to fit. The 8 cubes have already filled up the entire cubical volume of the image; where else is there space for the inside of the hypercube?

The answer should be clear if we apply dimensional analogy: there is 4D depth involved here. The inner cube is deeper in the 4th direction than the outer cube; so there is ample room in between for the inside of the hypercube. In fact, the amount of room available is the sum total of all possible cubes lying between two opposite cubes, as shown by the following animation:

The magenta frustum is actually a cube moving back and forth between the left and right cells of the hypercube. It traces out the 4D hyper-volume enclosed inside the hypercube. Notice that it appears to be turning inside-out as it crosses the middle of the hypercube. As we've explained before, this is an artifact of the perspective projection used to create this animation; the cube is not actually turning inside-out. This does mean, however, that 3D volumes are “flat” in 4D, so a 3D cube behaves like the equivalent of a plane.

Try to compare this animation with the 3D one carefully, and see if you can see the analogy between the two. It is important to understand that each different apparent shape of the magenta cube represents a distinct slice of the hypercube. The volumes occupied by the magenta cube at different displacements do not overlap! As 3D beings who have little knowledge of 4D, this can take a while before it “clicks”. But it is worthwhile to make the effort to grasp this. It will yield much insight into visualizing 4D.

Cells, Ridges, Edges

The upshot of all this is that in 4D, objects have a much richer structure than in 3D. In 3D, a polyhedron like the cube has vertices, edges, and faces, and fill a 3D volume. The cube is bounded by faces, which are 2D. Pairs of faces meet at an edge, which is 1D, and edges meet at vertices, which are 0D.

In 4D, objects like the hypercube not only has vertices, edges, and faces, but also cells. A 2D boundary is insufficient to bound a 4D object. Instead, 4D objects are bounded by 3D cells. Each pair of cells meet not only at edges, but at 2D faces, also called ridges. The ridges themselves meet at edges, and edges meet at vertices.

The point is that in 4D, 3D volumes play the role analogous to surfaces in 3D, and 2D ridges play the role analogous to edges. Because of this, it is important to visualize 4D objects by thinking in terms of bounding volumes, and not 2D surfaces. A 2D surface only covers the equivalent area of a thin string in 4D! When you see a 2D surface in the projection of a 4D image, you should understand that it is only a ridge, and not a bounding surface.